In the opinion of Dr. Allison Sekuler, president and chief scientist at the Toronto, Ontario-based Centre for Aging + Brain Health Innovation (CABHI), we are now living in “the most exciting time, from a scientific research and innovation perspective, for ageing and brain health that I have seen … It is probably the first time in our history that people, when they think about dementia research in particular, have hope.”

Sekuler believes that detecting and preventing age-related sensory and cognitive decline with new scientific discoveries, technology, and artificial intelligence (AI) has the potential to dramatically reduce the toll taken by Alzheimer’s and other dementias.

“There is a coming together, a collision, if you will, of different findings in science,” Sekuler said, “but also different kinds of technologies. And there’s an increased recognition and awareness that there is something that we can do about dementia.”

CABHI, which Sekuler described as an “innovation catalyst,” promotes collaboration among innovators, researchers and end users, and funds development of promising technologies and approaches. For instance, CABHI’s Discover + Adopt program, which funds and trains organizations to implement innovations, enabled Canadian provider Perley Health to implement the Tovertafel interactive projection system to engage residents living with dementia in activities and social interactions.

CABHI’s parent, Baycrest, is an academic health sciences centre but also an aged care provider offering independent living, assisted living, and long-term care for more than 1,000 residents, and it also includes a post-acute hospital specializing in the care of older adults. Baycrest’s other research and innovation subsidiaries include the Baycrest Academy for Research and Education (BARE) and its Rotman Research Institute, which does clinical, cognitive, and computational neuroscience research on ageing and brain health. Along with her leadership of CABHI, Sekuler is also president and chief scientist of BARE.

Putting brain health research into perspective, Sekuler said a lot is at stake: “If we actually live up to the predictions of doubling the numbers of people living with dementia by 2050, our health care systems in the United States, Canada, and around the world [are not] ready for that.”

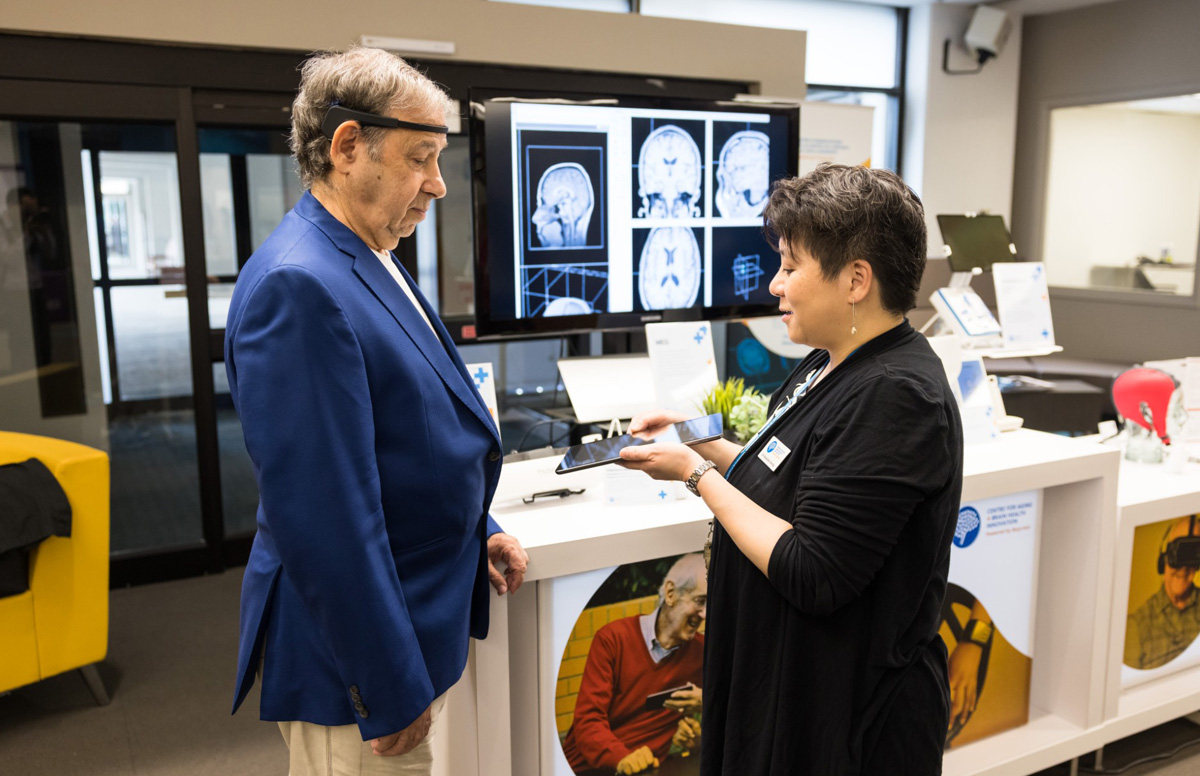

She is encouraged by research into combinations of drug therapies, lifestyle changes, and brain stimulation, which she said is becoming increasingly available as a commercial product. She also cites new blood tests, vision tests, and other kinds of biomarkers with potential to detect, early on, when someone is on the path toward dementia, along with neuroimaging, which she says can now be done with portable MRI machines. Slowing the average age of onset of dementia by five years, she said, could decrease its prevalence by up to 50%.

For Sekuler, bringing “precision ageing” to the lives of those living with dementia is the goal. “We want to make sure that everyone, whether they are at risk for cognitive decline or they’re living with a form of dementia, is living their best possible life. And for that we have to personalize things. I think that’s where so much of the work is headed, and it’s one place AI is going to be really helpful,” she said.

Appreciating the central role of professional caregivers in improving quality of life for those living with dementia, Sekuler advocates for ensuring they build an understanding of ageing and brain health itself, as well as the technologies being developed. “From the innovation perspective, we need to make sure that there’s an awareness of the technologies [among direct caregivers] so that they will be more accepting of them. We see a huge potential for this kind of training amongst professionals.”

For family and other informal caregivers, Sekuler said, “the challenge we see … is they don’t really know where to go. I’m preaching to the choir here, but for every person diagnosed with dementia, two or three are diagnosed as caregivers, and it really upends people’s lives.” She would like to see more consolidation of information from trusted sources, and formal learning that can be done virtually. The virtual programs Baycrest leads, she said, have been very successful, and also help caregivers with their isolation, noting that the risk of developing dementia can be as much as six times higher for informal caregivers: “It’s not because it’s contagious. It’s because you’re not sleeping, not eating well, not exercising, not socializing … not doing all the things we can do to decrease dementia risk.”

Sekuler will attend the 2025 LeadingAge Annual Meeting and Global Ageing Network Biennial Conference in Boston, Massachusetts, November 1–5, and participate in the Global Ageing Summit on 1 November, presenting on promising work in brain health. She also sees the conference as an opportunity to meet providers and learn their pain points and needs: “Understanding the community’s needs and concerns helps us reimagine what our programs ought to [look like] and think about how we can create the right sort of partnerships.”